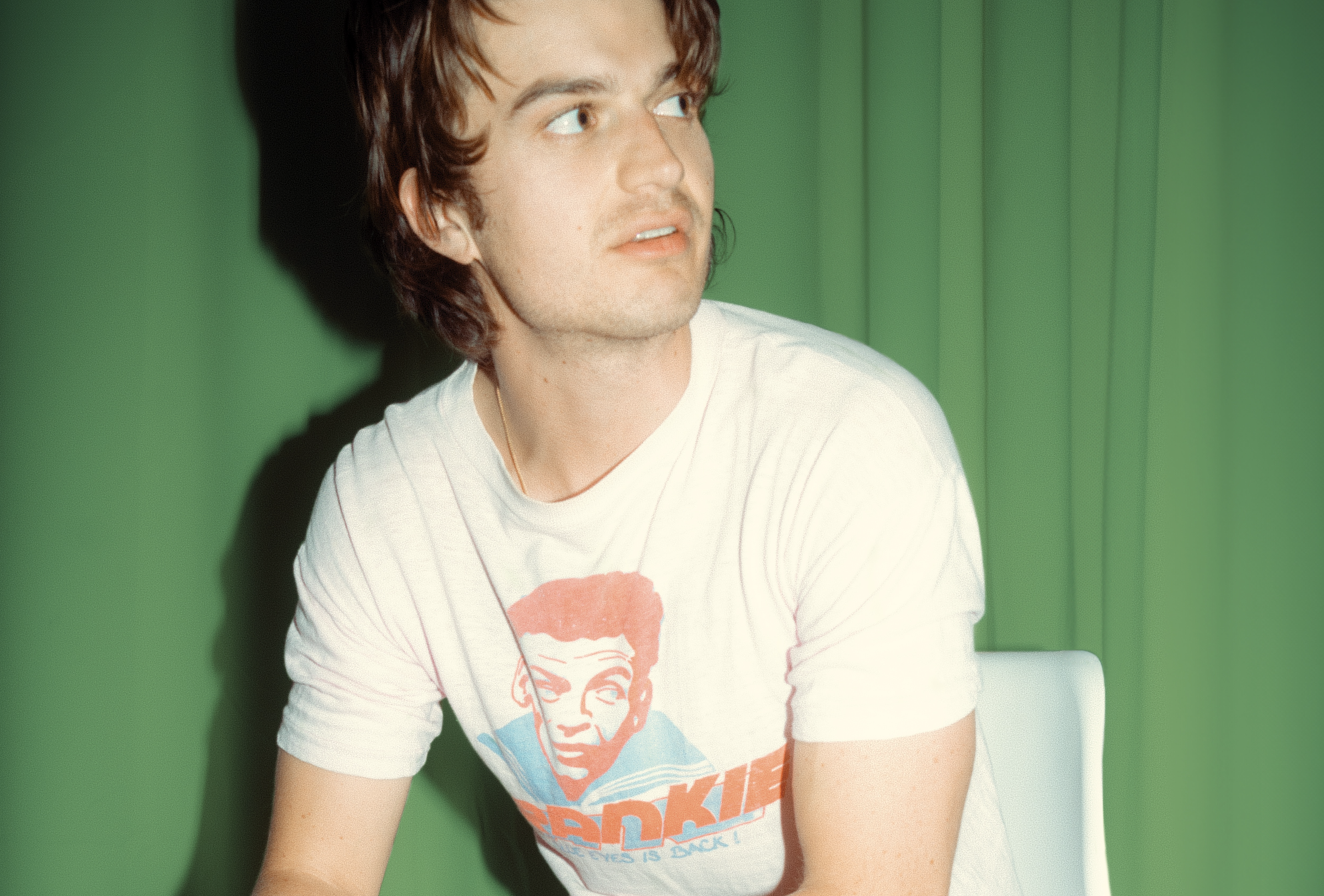

Die Maccabees sind nach über zwei Jahren mit einem Knaller von einem Album zurück. ‚Marks To Prove It‚ ist eine sehr direkte Ansage, es ist energetisch und mutig. Die Fragilität, die bei den Maccabees immer mitschwingt, geht trotzdem nicht verloren. Wir haben Hugo, Gitarrist und Bruder von Frontmann Orlando, vor dem Konzert in Berlin bei strahlendem Sonnenschein auf einer Parkbank getroffen und mit ihm über die neue Platte, übers Live-spielen und über die Hürden während des Schaffensprozesses gesprochen.

The record went to number one in England, congrats!

We couldn’t have hoped for that. It was almost a shock, you know, it never happens, we never get number one. So that was really, really good and hopefully that will help us out in Europe.

First of all, I think you did an amazing job with the new album. What’s quite prominent when you compare it to ‚Given to the Wild‘ is that ‚Marks to Prove It‘ feels much more direct and band centred. Did you feel like you had to lose some of the cinematic, monumental sound to make room for something new?

Yeah, we started writing new songs straight after finishing the tour they all sounded quite like the last record, like ‚Given to the Wild‘. And actually, it took us quite a long time to change our mindset, because we were so used to working in that way. You know, we didn’t feel like we had found the new route, really. We spent six months doing that and then realised that if we’d change the way that we wrote the songs, then we’d end up with a different thing. So we stopped using computers, cause on ‚Given to the Wild‘ we had started doing that. There’s programmes like Logic. Everyone uses it to do demos now – because it’s so good, you can have so many instruments, you can use strings, everything you can add. But then it means that the demos are really complicated and then when you try and make something that doesn’t sound like the demos, when you take away the elements, you’re left with something that doesn’t feel like it was right anyway. So actually, we just put one microphone in the room and then just rehearsed all day, every day, not allowed to record anything. So that’s almost more of a normal thing to do, it’s not a new idea. But for us it felt like a new idea. And that’s how we did the first record and the second one, so actually just kind of going back to that. And then there were moments on the record where we did get in to a little bit more details and it meant that those moments were more important. It all came together in the end. It was two years of work.

You’re now playing live again after this intense phase of writing and recording. What is that like with regard to the new album specifically and the live approach you had making it?

It’s a great feeling cause this translates so well. Playing live in general is obviously good because it’s predetermined, you’ve already worked it out, you know what you’re gonna do and you can enjoy it. But with the new record, playing live feels much more like a logical solution to recording it.

Were there any moments where you were losing the distance to judge if you were on to something good or not?

We had our own studio for the first time and we were spending so much time there. We weren’t playing gigs, so we just had this one place, always the five of us. It can get quite claustrophobic. And everyone goes through bad days and good days and you go through a lot of doubt whether the new stuff is good or not. We just worked and we didn’t stop until things got clearer. But we were very lucky to have our studio cause if we didn’t, we wouldn’t have been able to put so many hours into it. And the fact that we put those hours in, I think, kind of shows in the record. Although it’s more simple in ways, it takes a lot time to get it simple.

You talked a lot about Elephant & Castle where you had your studio. How come that this area had such a big influence on making this record?

There’s a sort of ugly honesty about Elephant & Castle. It’s not impressive in the sense that it has a lot of pretty, shiny things to offer. But I guess it has a concrete charm about it that clashes with what’s going on there now. It’s changing now and it’s losing it’s identity in a way. Gentrification is kicking in. We sort of peeled back the layers of this area bit by bit cause we were there so much. In the beginning we didn’t really link the process of making the record to where we were. But then we realised that it was almost an anchor. Living, cause we all sort of live in the area, working there, everything in this one place. This realisation gave us more clarity for the album, if that makes sense.

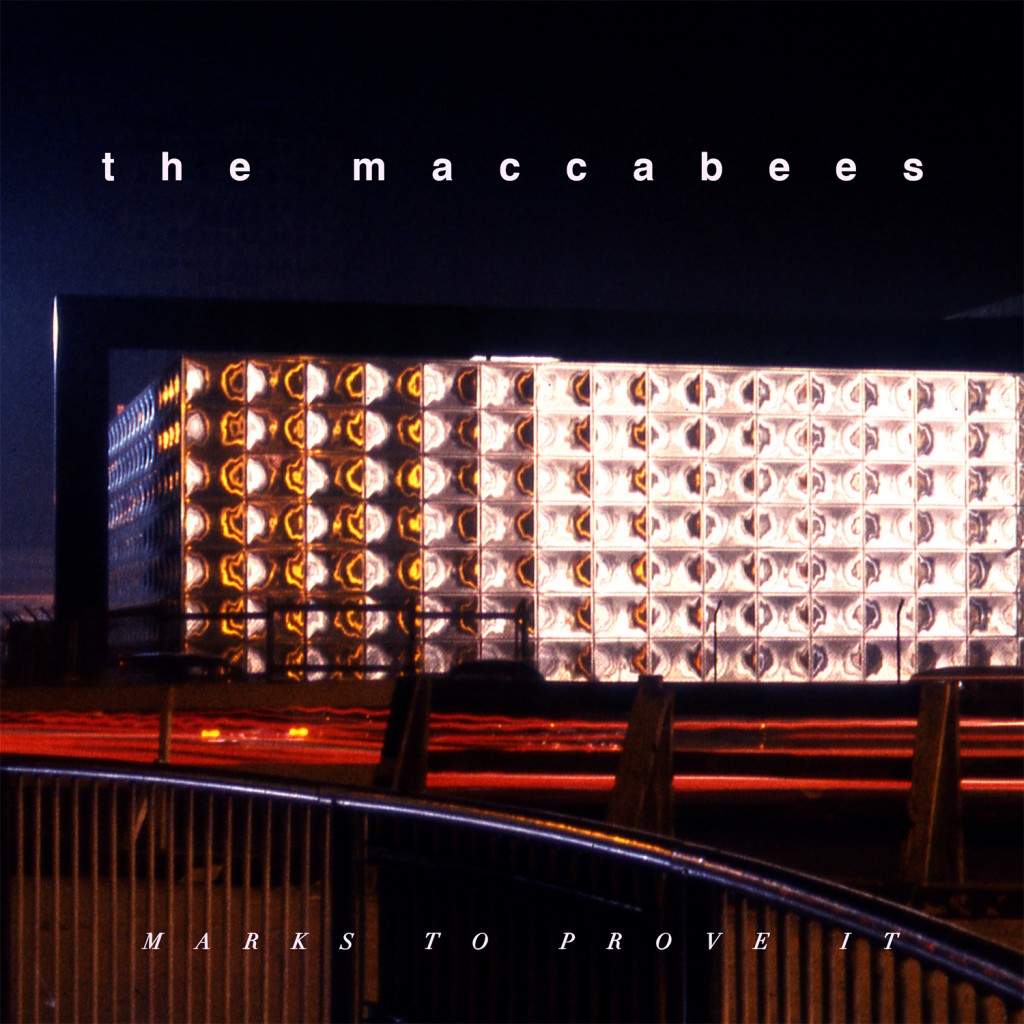

And the album cover is a photo of a memorial in the area, right? What made you chose this?

Just down the road from our studio, in the centre of a roundabout which is the main feature of the area, there’s this memorial building, Faraday memorial. It’s been there for a long time and we never thought about using it at all as the artwork. But we were looking for something that had some way of showing what the themes of the record were about. And then Orlando stumbled across that photograph, which was just a one off photograph taken by an amateur photographer in the 70s or 80s when it was first built. I think it just summed up everything that we wanted, that it’s a really straight forward, simple thing that you could quite easily ignore – and we do every day. You know, you go past it every day, everyone goes past it, but not everyone stops and says „That’s a really lovely thing“. Most people just ignore it. So it’s sort of bringing people’s focus to see what is good about something that you wouldn’t normally acknowledge.

So that’s why you went with ‚Marks To Prove It‘ as the title of the album? It’s perfect! At which point did you decide that it would fit?

Yes, exactly. It just works, it’s a sort of symbol of the change that’s happening there. But we decided this late on. We had the song and that was the name of the song. And during the recording process we had the thought of ‚Marks To Prove It‘ would be a big title, a good title. But we had doubts about calling it the same name as the song, the first single. So we tried for ages, we had that one in the background and we tried to come up with another title. And we just couldn’t find anything that would fit it better, so we went with that. Amazingly, it all falls into place at the end, you know? Cause there are so many moments where you go „none of it makes sense“. It’s really nice when people do say to you „it’s amazing“, cause the whole thing makes sense. You never know, really. You think it does, but then you don’t know if other people notice.