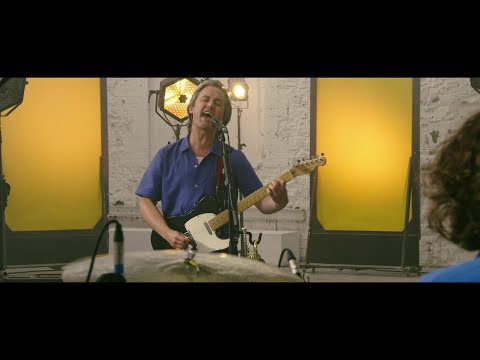

Foto-© Rich Gilligan

Foto-© Rich Gilligan

Letzten Freitag erschien das fünfte Studioalbum des irischen Projekts Villagers bei Domino. Mit Fever Dreams gelang Conor O’Brien eine eskapistische Platte, die elektronischer, nuancierter und vielschichtiger ist als ihre Vorgängerinnen. Geschrieben wurden die Hauptteile der Songs im Laufe von zwei Jahren, aufgenommen wurden sie in einer Reihe von Full-Band-Studio-Sessions Ende 2019 und Anfang 2020. Während der langen, entschleunigten Pandemie-Tage verfeinerte O’Brien sie in seinem winzigen Heimstudio in Dublin. Gemischt wurde das Album von David Wrench (Frank Ocean, The xx, FKA twigs). Wie in einem Traum arbeiten die Songs mit Versprechungen, Widersprüchen, aber auch Euphorien. Emotional, flirrend und zukunftsgewandt ist der neue Sound, der Villagers ausgesprochen gut steht.

Wir sprachen Anfang August mit O’Brien per Zoom über die neue Platte. Im Interview erzählt er, was für ihn die Atmosphäre in Fever Dreams ausmacht, wie es zu dem aufwändigen Artwork zum Album gekommen ist und wie er versuchen will, den neuen Sound in Liveshows zu übersetzen. Außerdem sprechen wir über die Gefahren einer digitalen Gesellschaft, warum Kunst auch dazu da ist, Widersprüche im Bewusstsein der Hörer*innen hervorzurufen und inwieweit seine irische Heimat ihn als Künstler beeinflusst.

Congratulations on your new album. It is your fifth full studio album. Has making albums ever become a routine job for you?

I do not think it ever has. Maybe if I think ahead to the next one, it starts feeling like a routine. But then I just get lost.

Are you always writing? Is that part of your daily life?

I have phases. I am writing at the moment, but it is very strange music. It sounds quite negative and dark. I do not really want to present that. There are always phases where you will write things and then you layer them with something else and then they will become something you want to present. It is always happening to some degree.

Are you ready to present Fever Dreams?

Oh yes!

Fever Dreams is a very fitting title for the atmosphere of the album, what is the sentiment behind it?

The songs feel aspirational. They are looking towards positivity, but they are delirious as well, because of all the craziness that surrounds them. That is what it is to me: a delirious aspirational feeling and wanting to transcend all this negativity around you. When I was making them, they gave me that feeling of possibility and that I could do anything. I was working a lot with the band and we put structures on things and then breaking the rules with those structures. That process of making it reminded me of the feeling of lucid dreams and that is why the title stuck.

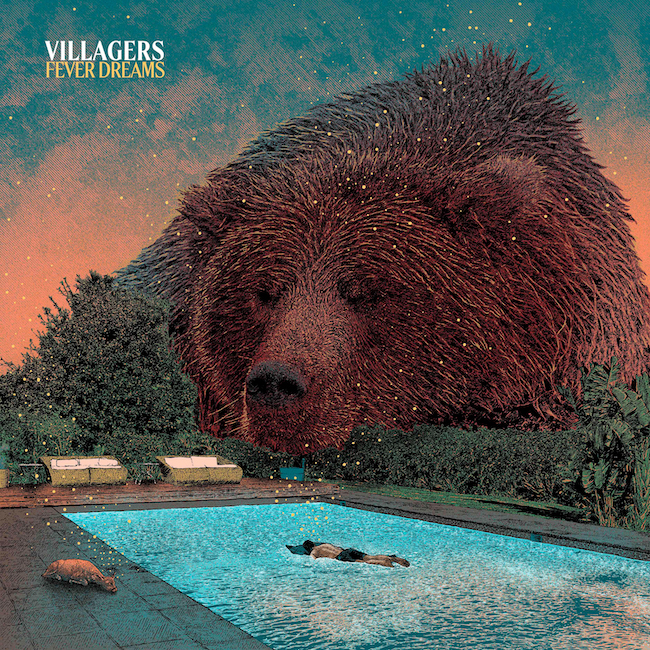

The art work plays with the concept of dreams and promises at night as well. It was inspired by the historical star signs of Ptolemäus. How do you connect them to your songs?

I’m not hugely knowledgeable about astronomy, but I get interested in it now and then. I like the idea of us trying to find patterns in the universe. It shows more about our psychology than anything else really. I like that as a metaphor for the patterns we try to place around us everyday. The artwork was a bit of a surprise though. I asked the artist Paul Phillips to draw something for the album and I sent him the songs The First Day, So Simpatico, and Fever Dreams. I told him that I wanted the artwork to represent scale, there needed to be an aspect of how tiny or large we are. He just strangely came back with the bear artwork and the guy in the pool. It was so strange, because that links in with Ursa Major, which is in one of the songs I did not send him [note: Song in Seven]. We then decided to do more album artwork based on the constellations and bring that theme more forward. It really worked and felt like a nice synchronicity that bubbled up quite naturally.

It is quite a bold move to invest so much time and also money into four different artworks and LP sleeves – meaning the physical and visible part of your music.

It is quite a bold move to invest so much time and also money into four different artworks and LP sleeves – meaning the physical and visible part of your music.

I love vinyl and I love records. That is a testament to my record label, they seem to still want to invest in the physical form of vinyl. I got them delivered yesterday and I have them here and I am smelling and touching them. It is very exciting for me, because the physical form of music is a document of a time. When everything is purely digital that changes. I have nieces and nephews and I like the idea of giving it to them and in 15 or 20 years time they can see it and be like, “Oh, that was my uncle’s album in 2020 and 2021, when Covid was happening”. I like tangible and physical products.

Sonically, you developed into the other direction though. With your last album came a big shift towards a more digital approach of music, now Fever Dreams is sometimes disruptive, less melodic, more layered. How would you describe your musical journey?

It does not feel linear. My second album had a lot of electronics and on my third one that was all gone. I remember when I was doing the first album, I still had my previous band on my mind. With this band in my early 20s, my music was more indie with an electric guitar and we all swapped instruments and jumped up and down on stage. After I have done all that it felt very exciting for the first villagers record to make acoustic music with maybe an organ. That was the aesthetic I was excited by. But I never left the more digital thing with synthesizer and so on. Before Covid and Lockdown we did about four or five full band sessions and recorded most of this album. As we were doing this, we kept building and building the songs and they became worthy of this bigger texture and vista. I wanted to give them as much as they needed and that required synthesizers, samplers, and lots of different things. The process was really fun and that’s the only way you can learn – by making yourself uncomfortable.

Villagers started as a solo project, now you’re working with a band, your website is called “wearevillagers”, but the public image of villagers is very much centered around you. How about the creative process?

It is mostly me, because no matter what we work on, I always take it home and bring it back to the band. But the guys are very instrumental on this album. Each player was doing his own thing. I was not dictating this much, but I was trying to shape the whole process in a different way. It involved more trust and was a much more social thing. My drummer at the time really spurred me on. There were certain songs I wanted to dump and he was trying to keep them. It was a really enjoyable process and I am hoping to keep that up in the future. I can get a bit too clingy to my ideas and when you are opening them up, you start to really know yourself and what you are trying to express. You start to question yourself and that is always very good, because it brings humility, which brings intellectual curiosity. These are the things you might not have if you are living in your ecocentric world.

The new sound also needs a new concept for your live shows. I imagine it to be quite challenging to bring together old and new aesthetics, but also to translate the complexity of the songs into a live setting.

The new sound also needs a new concept for your live shows. I imagine it to be quite challenging to bring together old and new aesthetics, but also to translate the complexity of the songs into a live setting.

It has been a lot of work. It has been extra hard as well, because we had to start rehearsals without vaccinations. We were trying to find large rooms and open windows. But also just figuring out the way to go with samples and things. Just figuring out how far you want to go with samples and how far you want to recreate the album or if you want to make a new version of the song which is live. We have gone with samples: I am playing trumpet live, but I am also using some saxophone samples, because it is such a big part of the music this time. We decided to go for that, because it represents the music properly. For certain shows, when we can afford it, we will bring real saxophones and violinos. We also have a different drummer now. The guy who drummed on the album is becoming a therapist. It has been an interesting trip so far, but we have only done a few shows. We have done some huge festivals a week and a half ago and it was dipping a toe back into the waters of playing live. That was exciting.

Your music is very emotional, but also very future-orientated, which I find remarkable as those two are often seen as contradictory. You have also spoken about the dangers of a digitized society.

Yes, I definitely do not want to look back creatively or in life. I think contradictions are quite important. In our waking world now, when we are on our screens all the time, everything has become so tribalistic. People are forming together in ideological groups on every issue now and they are not listening as much. It makes you not able to keep contradictions in your brain. John Keats used to call it negative capability, which is the ability to keep two contradictory concepts in your mind and use them. That is the basis of creativity. You realize that you do not know that much, but you can learn from opposing people and civil dialogue between opposing viewpoints, even in your own mind. We are at the very beginning of the strange internet age and I think creativity can fight back against it a little bit.

When I prepared for the interview, it seemed like every article about you is also about you being Irish. How much does your home define you as an artist?

It is the same with nearly everybody. Your relationship to your home, to where you are born, is never simple. There is probably a lot going subconsciencly on that I do not know. The music I make is probably influenced by a lot of stuff from when I was very young that might be Irish based. We just did an American television show a few days ago and one person said, “Oh, I recognize this guy’s voice from the tv show Big Little Lies, it is so Irish”. And I thought, “Really?” I do not think I sound so Irish, but maybe I do. I do not sound like many Irish singers I know, but maybe I am not hearing it. Ireland has such a unique and complicated history for this part of the world and generationally that is always going to seep into your psychology. Just now in my 30s I can start to see all the things I thought were innate, that perhaps were more culturally learned from my parents. Also, we have this international image of being these cheeky little outlaws, who are not the UK, but have this very fractious relationship with the UK. I think these very complicated and nuanced things creep into your art. Even on a very basic level. If I was English, Scottish, or Welsh, I would have grown up watching British television and getting British cultural signs and signifiers. Whereas growing up in Ireland, I grew up getting British television cultural signs and signifiers AND Irish television and seeing how Irish people were depicted in the 80s, 90s, and 2000s on British television while also seeing our own television. That instantly is a big difference, because you are already getting a sense of contact that will feed its way into your internal narrative.

Thank you for the interview!

Villagers Tour:

18.01.2022 Hamburg, Fabrik

19.01.2022 Berlin, Metropol

21.01.2022 München, Technikum

23.01.2022 Köln, Kulturkirche