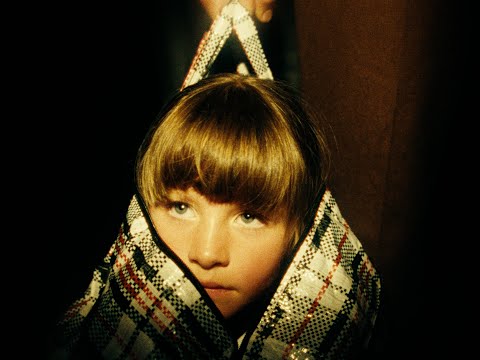

Foto-© Atiba Jefferson

Foto-© Atiba Jefferson

Die Briten von black midi entwickeln sich seit ihrem Debüt Schlagenheim aus 2019 in rasender Geschwindigkeit zur Speerspitze einer ganzen Szene, die dem altgediente Rock-Genre mit frischem Blut, unbändiger Kreativität und wilden Genre-Mixen neues Leben einhaucht. Und wer ein ordentlicher Newcomer und Rock-Erneuerer sein will, ruht sich natürlich auch nicht auf seinen Lorbeeren aus, sondern legt nach dem Zweitwerk Cavalcade aus dem letzten Jahr diese Woche direkt das nächste Album Hellfire nach. Wir sprachen mit dem Drummer Morgan Simpson über die gierige Getriebenheit des Trios, die Intensität und Dichte des neuen Albums und wie es ist, wenn man auch nach drei Jahren Tour noch Spaß auf der Bühne miteinander zu haben. Unser Interview!

This album comes so soon after the last one – are you guys working on stuff every day? How has your process of writing such esoteric songs developed to the point where you can release an album every year?

Comparing Schlagenheim to Cavalcade and Hellfire is like day and night in terms of how we went about writing them. The first record was far more jam based and most of it was written with all four of us in the same room in a sort of design by committee style. Which is something I think some bands do, but we would spend a lot of time deciding which chords should go here or there, and it ended up being more counterproductive than productive. Especially with the amount of touring we were doing in 2019. I think the bands that don’t do that do it for reasons that we discovered when we were doing that. Sometimes if we are sound checking and someone is playing a cool idea, another person might join in and then we will record it and maybe make something of that, but that’s the closest we come to writing on the road. With the second record and the time we had weirdly given to us during lockdown, I think it gave us a chance to reset and rethink about life and think “what do we want to do with this thing we call music?”. Do we want to be pigeonholed and please other people’s ideas of what we should be as a band and be a post-punk band or post-rock band, or shall we just try some stuff and if it works, it works, and if it doesn’t, it doesn’t, but at least we tried? In isolation Cam and Geordie were writing songs and some of them were almost fully formed but a lot of the ones that weren’t there was a lot of space for different moulding and fleshing out those songs into different things. I think we just found that it works better for the band, and we have always said we want to release as quickly as we can, not for the sake of it, but because we believe that an album is only a documentation of an artist at a certain time, so we don’t see the point in sitting on music for ten or fifteen years. We just want a snapshot of where we are at this place in time. It’s just how we work, and we work quickly.

The intensity and relentless density on Hellfire are even more heightened than on Cavalcade – is it possible to go even further? A lot of the conversations around Black Midi are focuses on influence, and I’m aware of potentially beating a dead horse on this one so I apologise. Is there anything that you guys have been obsessing over lately? Have you been watching or reading Dangerous Liaisons?

The intensity and relentless density on Hellfire are even more heightened than on Cavalcade – is it possible to go even further? A lot of the conversations around Black Midi are focuses on influence, and I’m aware of potentially beating a dead horse on this one so I apologise. Is there anything that you guys have been obsessing over lately? Have you been watching or reading Dangerous Liaisons?

[Laughs] I know Geordie had read it and watched it quite close to when we were writing that song. At the time of recording, I was in a big Stevie Wonder phase. I find myself every couple of years coming back to those supposedly classic artists or albums. I found myself thinking, I have listened to the Stevie that everyone knows from like 1972-76, but there is so much more. Even before the Motown stuff when he was paying a lot of homage to Ray Charles. Essentially what I did was start from the first record and went all the way up to Hotter Than July. And through that process, it further reinstated what I believe, which is that he is the greatest songwriter of all time. Hearing something like ‘Ma Cherie Amour’, and then ‘Contusion’. You know, ‘Ma Cherie Amour’ is at the back end of his Motown sound and then ‘Contusion’ is a mad jazz fusion track that sounds like it should be Jeff Beck. I find it really inspiring to see that journey from someone who was so much the poster boy of Motown and then came to a crossroads where it was a bit stick or twist for him because he could have continued with that Motown sound that everyone was familiar with and he probably would have done a great job with it but he chose not to and he said to Motown “I want to do something different, and either you guys support me or you don’t but I’m going to do it either way.” That sort of let him to create an amazing record called Where I’m Coming From, which came out in 1971 and is probably my favourite of his. It has ‘If You Really Love Me’ but that is sort of the only well-known track on the record, but I just love it because it is sort of the transition period from the Motown sound into Talking Book and that whole era. It related to me going to see a film at that time too called Summer of Soul. That was an amazing experience. I can’t even describe how I felt watching it. I saw it three times in the space of a week because I just thought it was the most incredible story and line-up of people playing. The thing I found ironic is that to me at least, when I think about Woodstock, and I think of the most iconic performances, I think of Jimi Hendrix, and I think of Miles Davis. Which is deeply interesting because they were playing for white people, which this totally other thing was going on. So, anyway, Stevie and a lot of Sly and the Family Stone and amazing black American music from the 60s and 70s really.

I need to go back to doing deep dives. I used to listen to an artist’s entire catalogue if I really liked them, but now it’s a lot of new music Friday’s and I spend less time with things because there are so many options.

It’s a different time we live in. Cam was telling me something like 60,000 songs are released every new music Friday or something like that. Firstly, that is too much for anyone to process, and secondly, it is released in a manner that doesn’t encourage you to really immerse yourself into that record. It’s a playlist that you can change at any time, whereas if you have a record, you spend time with it, you really have to attend to it.

Agreed. How do you decide on the sequencing? Do you deliberately give the listener breaks with sweet songs like Still, which by the way sounds like no other black midi song, I’m a big fan?

With this record, there was a bit of a throughline and a theme that was present. I think that selected itself in terms of where we were going to go with the narrative of the record and prior to even getting in the studio we had a relatively good idea about what the track listing might be because we had two days of rehearsal before recording where we learned the newer songs that were written. Having a relatively clear idea of what direction the record is going to go in means the recording process is easier in terms of knowing energy from track to track and how we are playing. On ‘The Defence’ for example, which we knew was going to be the penultimate track, or the sweet bubble gummy track before ‘27 Questions’, you can keep that in mind before you go in to do the take. I think generally we have always liked to have fun with sequencing.

You guys have such strong closing tracks – Ducter and Ascending Forths are both such memorable finales and I think you’ve done that again with 27 Questions.

In a lot of ways, the songs pick their own position on the album, because we always want to make them distinct from the others and not feel samey. We knew what we were doing with 27 Questions.

The Race is About to Begin is a top 5 black midi song for me – most of your music is claustrophobic or conjures images of underground basement shows, but this one opens up into a sense of big space with lots of reverb. What were the seeds of that because, while I don’t think anything is off the cards on a black midi record, that was very unexpected, and you pulled it off?

The Race is About to Begin is a top 5 black midi song for me – most of your music is claustrophobic or conjures images of underground basement shows, but this one opens up into a sense of big space with lots of reverb. What were the seeds of that because, while I don’t think anything is off the cards on a black midi record, that was very unexpected, and you pulled it off?

The verse idea came from a jam that Geordie and I were doing about a year ago, and as I say about ideas that do come from jams, you know immediately when something works. I remember looking at Geordie and laughing because it sounded like something from Looney Tunes or Mr Bean walking down the road. It felt comical in that sense. Eventually over time it became what a lot of people will hear, but because the track itself is so dense, I think we tried to maximise the tool of production and make it sound a bit more open and like it was pulsating. Not like you were gasping for air, but like you were breathing very deeply, that was something we were aware of because it would have been easy for some of those parts to get lost, but I think we just tried to use the extremes of things being quiet and dry and then things just opening up and it feels like you’re in a cavernous hall or something.

It’s cool that you laugh a lot when you play together. I think it’s pretty funny to be able to play so ridiculously well, and it seems like you guys play with that in a humorous and irreverent way. Is it part of the sound of the band you guys challenging yourselves to play even more virtuosic? Do you enjoy pushing yourselves technically, or does it come naturally?

One thing that’s always been a pillar of the band is to push ourselves in every way possible and I guess the most obvious way to do that is on our respective instruments. It has always been present. During the first record’s release there were a lot of misconceptions of the band, and I think a lot of people just thought we were doing it to show off or to show how well we can play but that couldn’t be more far from the truth really. The truth is that it just come out – I think there is a conscious decision to challenge ourselves technically in the music, but not in a way that is contrived in any way. A lot of our influences and things we listen to are technically challenging and it honestly just comes out in the music. The reason why we do laugh a lot of the time when we come up with ideas is because there is not better feeling that when you’re playing with someone that you feel on such a similar level to, and you play something that is so not what you thought you would be playing an hour and a half ago when you started jamming. You might be playing something challenging and technical, but you almost feel like you’re on a cloud because there is that connection and relationship. It almost feels like you’re not even playing. I think that’s the best feeling as a musician, and I get that a lot from the band.