Foto-© Emma McIntyre

Foto-© Emma McIntyre

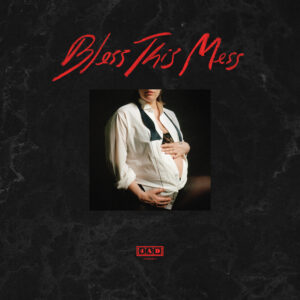

Meg Remy hat sich mit ihrem musikalischen Alter Ego U.S. Girls in den letzten Jahren zu einer der kreativen Kräfte der Torontoer Szene entwickelt! Von den ersten Anfängen in Kellern in Philadelphia und Chicago, als sie durch Delay-Pedals über rohe Loops summte, hin zur selbstbewussten Frontfrau eines achtköpfigen Art-Soul-Orchesters, das die Welt bereist, hat die Vision, sowie das Talent Remys das Projekt über die letzten 15 Jahre zusammengehalten und geprägt. So wurden ihre drei letzten Alben Half Free, In A Poem Unlimited und Heavy Light alle für den kanadischen Juno Award nominiert und standen auch jeweils auf der Shortlist für den Polaris Prize. Mit ihrem nächste Woche bei 4AD erscheinendem Album Bless This Mess öffnet die multi-disziplinäre und experimentelle Pop-Künstlerin nach zweijähriger Abwesenheit, verbunden mit der Geburt von Zwillingen und der Veröffentlichung ihres ersten Buches Begin by Telling, nun das nächste Kapitel ihrer Erfolgsgeschichte. Wir sprachen mit ihr über Zoom – unser Interview!

There are no other bands, at least that I listen to, that sound like US Girls. Since I first heard you back in 2015, when you released Half Free, I’ve been following your music pretty closely. I’ve always associated it with the uncanny. These kind of domestic spaces made uncomfortable. You’re such a skilled storyteller and you always make really kind of bold choices in terms of influence and arrangement that are playful and dark, but always very political. While Bless This Mess is easily identifiable as a U.S. Girls record pretty quickly, what’s different about it is that it feels slightly more optimistic. Do you agree with that assessment?

It’s really interesting because I heard that from someone else yesterday, too. And it really it was surprising to me because I can see it being perceived that way. And I think, like maybe on the surface it maybe it would appear that way. I think for me personally I’ve just grown more okay with uncertainty and uncomfortableness. So it’s like not an optimist or a pessimist thing. It’s a this just is thing. I’m taking it less personal. It’s not some sort of reaction to anything I’ve done. Kind of accepting that I don’t really have much control over anything, that has been a positive tool for me to have for my kids, you know, a very useful tool.

The only reason that I said that is because it does feel like a kind of coming to terms with the coexistence of beauty and sadness in the world. And it’s not as angry as In a Poem Limited, or as grieving as Heavy Light.

Yeah, I’m definitely not angry. I’ve let a lot of anger go. For some people anger is a really useful tool. It can be a fuel to get them to act or change something. For me, it wasn’t. It made me make a lot of art, but it wasn’t good for my body and my soul. And I think sometimes when you’re really angry, you’re convinced that you’re right because you feel something. It feels so passionate and urgent that you must be right, you know? And I think with anger, you’re not able to hear other perspectives. That was something I wasn’t doing enough of. I was really just kind of cemented in my perspective, in my anger.

You almost have mantras on this album to remind you of that: the “breathing in/breathing out” on Futures Bet. It’s almost like a mindfulness mantra.

Yeah. I remember saying to my vocal teacher, who’s like, a very funny woman, I was like: I’m thinking about getting the word “breathe” tattooed on my hand. She was like: “oh, don’t be one of those bitches” [laughs]. And I was like: “yeah, maybe not”. It’s very interesting how mindfulness can also become just a way to sell things. When I’m feeling really mindful, there’s nothing I could buy or think of buying. It really collapses the marketplace, it collapses desire, and I find it very funny, but also sweet and understandable, how mindfulness and this kind of wellness situation has gotten totally taken over.

One of the things I really want to ask you about is your humor, which is a defining characteristic, I think. We have to talk about Tux, which is a song written from the point of view of a dinner jacket. And there’s also Screen Face, which is my favorite song on the album. It has this hang out vibe that feels like it came from a stoned conversation or something. It’s got a wonderful, everydayness about it. Where does humor fit into the writing process? How important is that to you?

One of the things I really want to ask you about is your humor, which is a defining characteristic, I think. We have to talk about Tux, which is a song written from the point of view of a dinner jacket. And there’s also Screen Face, which is my favorite song on the album. It has this hang out vibe that feels like it came from a stoned conversation or something. It’s got a wonderful, everydayness about it. Where does humor fit into the writing process? How important is that to you?

I find it’s extremely important for not getting too high on my own supply. You know, I find that humor keeps me grounded. It keeps me real. I had this idea – and I don’t know where it came from, maybe from being inundated with the past and artists and icons – that you have to be mysterious to be a good artist. And I don’t like that because that’s not really who I am. I’m extremely talkative and like I like to laugh. And humor has gotten me through some of the hardest times in my life. Humor’s also just been a way to break apart really complex topics. Splinter them and laugh at different parts and make jokes and pit them against each other and play with language. Laughing at myself is then so important to my personal healing and growing and being able to take risks and go on stage and act like a fool. Laughing on stage was a huge development for me. It’s extremely important and I appreciate you seeing that thread. I think the music that I make, if it didn’t have humor, would be really hard to swallow. I think it would be like so pretentious that I most likely wouldn’t be sitting here talking to you.

Where did Tux come from?

When things were locked down and my mind was wandering and thinking about all the things that had become useless or obsolete during that time, like people’s closets full of clothes. When you see like a walk in closet with so many shoes and all of those things. It made a lot of objects seem very silly. And the tuxedo just really stood out to me like: “who’s wearing a tuxedo right now?” I’m sure somewhere in the world, tuxedos were still being worn, like on yachts and stuff. The uber wealthy, their world didn’t stop with COVID, I don’t think. But my husband and I are always talking about consciousness, you know, like everyone agrees that humans are conscious and some animals are conscious, but not all. Are bugs? Do rocks have consciousness? This kind of thing. It just got me on to clothes and imagining an outfit very sad in a closet, that wasn’t being worn, and it can remember when it was worn and where it went and how its owner’s body felt. Once it was there, it was so easy to write because it was humorous, you know? When you’re using humor, there’s no limits. You’re not trying to stick to some poetic parameters or abstract language or anything. It was very fun to write and I think that the results are so strange.

When I first heard that song, I laughed out loud multiple times. You’re definitely drawing a lot of lines to embodiment. It is one of the most foregrounded themes on the album and I would be remiss if I didn’t talk about motherhood and pregnancy with you. You’re pregnant on the album cover. You’re now the mother of twin boys. You’ve said you wanted to capture how your body and your voice were changing during the pregnancy. You sampled your breast pump on the song Pump. You’re even holding your newborn children during some of the vocal takes, which I think is very sweet. And we perhaps don’t have enough time to talk about your lyric essays Begin by Telling, which in their own way inhabit the language of the body. But can you just talk a little bit about your focus on embodiment and how that manifests itself in the form of the music? Because this is dance music!

I think that like embodiment is something that I’ve been working on personally for many years at this point. The record or the record previous to this, Heavy Light, was all about that because it was recorded live. So I had to prepare my body to make that record because there was no redoing something. There is no punching in to fix something. So it was all about getting in the body and shutting the mind off and doing the thing right. And the body informed the music and how it was recorded. Everything was coming from 20 bodies in a room, literally, all working in in concert with each other. This time around, making this record, it was forced embodiment because it was concurrent with the pregnancy. I now could not ignore my body because there was two lives inside of me that were depending on me eating 3000 calories a day. So my embodiment became tied up with two other people’s bodies, having like three hearts inside my own body. When I’d be lying in bed with my husband we would think about that, that there’s four hearts in the bed right now that are beating. the process I was going through was not only affecting what I was writing, but how I could perform the songs, right? When you get pregnant, your diaphragm gets just crushed. You can’t breathe down the way you did, which a big part of vocal training, finding your diaphragm, understanding how to open it and when, how to get as much air as possible, when to breathe. That was all out the window. Now I’m we’re preparing to play these songs live and it’s a very wild thing to be translating for a not pregnant body to sing these songs. It’s way easier for me to sing these songs now, and when I’m listening to the songs and I’m performing them now, I can feel my previous body that was kind of hijacked by the pregnancy. Now the songs in my body feel totally free. When I start singing them, I might start floating because I’m so light compared to how heavy I was writing them. Everyone has a different form of embodiment because everyone has different abilities with their bodies. Some people don’t have legs, you know, that doesn’t mean that they can’t dance, that they have no rhythm. I think dance music is the perfect thing for uniting bodies because it affects your blood, your heart. I’m answering all around your question but I’m excited to play these songs live and affect people’s heart rates live and see it. I feel very attuned to physical cues now, particularly flush cheeks and dilated eyes and things like that. I’m watching people’s bodies all day long with my kids. I’ve learned so much about physical cues and things that will be useful for me on the stage performing this dance music and trying to get people to get embodied during the show.

You’ve talked about James Brown and how he’s completely engrossed in the performance. And that’s a state that you really crave and would like to get more even in your daily life. There’s definitely a connection to be made between embodiment and immediacy and sincerity as themes of the album. But at the same time, there’s a tension because your music is so referential and so self-aware. I wonder whether you find that sensibility to be at odds with losing yourself in the moment of playing.

I don’t find it with playing. I think losing it in recording, that’s more difficult. But also, like we were saying earlier, everything is going to have its duality. So my sincerity is going to have insincerity right next door to it, always at all times. Letting go is also being strangled as well. And I feel that about James Brown. Like James Brown, he was lost in his performance. He was totally free. Yet he was so attuned to what his musicians were doing, he could find them on stage. So it was he was doing both. I don’t think one is ever able to just be one thing. It’s just not possible. It’s interesting to strive for. Maybe some kind of monks have achieved it on a mountaintop somewhere, but that’s because that’s all they’re doing and they don’t have contact with other humans. If you’re in contact with other humans, it’s impossible to just be one directional. I haven’t been able to achieve it, but I have been able to achieve on stage and a few times in my personal life, moments of complete embodiment where that’s all there is in that moment. I’ve definitely had it onstage. I’ve had it having sex. I think it’s the key to having sex. Thinking and sex are probably the worst combination, I think.

In a way, you’re saying that contact with other people and external stimulation are at odds with that kind of experience of complete embodiment. Another one of the elements of your recent music is a huge amount of collaboration. You finish the album by addressing everyone and the things that we have in common. There’s this theme of shared experience. You have I don’t even know how many collaborators on this one. Your husband, Max Turnbull, is kind of a lot of the band, but Alex Franco from Holy Ghost! is on this, Roger Manning, and a bunch of other people. What are your feelings about collaboration in the sense that this is almost your ever changing supergroup now?

I’ve been doing this for 15 years now, the first U.S. Girls record, I made in 2007 alone. And my skill set hasn’t changed that much in that time. If I didn’t want to be making the same record over and over again and having the same experience making the record, I needed to work with other people. And once you start working with people, your ideas can grow more ornate because you know the people that have the skills to be able to build that thing that you want. So it’s also been essential to me, that it’s not the Meg show. If it was just me, it would be boring for me. Same with playing live. The way things are right now, everything’s so precarious, everything’s so expensive, even thinking about bringing a band on the road is ridiculous. If I was smart, I would just have tracks and I would sing over them because it would be really low overheads. I’d make money and maybe no one in the audience even cares as long as it sounds good, but I can’t do that. It will be so boring for me. I want to be challenged. I want to work with people. I want to respond in real time to instruments. I want that feeling. I don’t want to settle for what would make the most money or be easiest or swiftest. Something I thought is really interesting is how you were reflecting back what I said about being in touch with other people can make embodiment difficult. I do think that’s true. In our day and age, it’s really difficult because it’s not even like we’re in touch with that many people. We’re in touch with avatars of people through screens. There’s nothing that I think is less embodying than being plugged into the net. And that doesn’t mean that there’s not things online that can help you be embodied. But I’m talking about just the average daily usage of like stepping up to the feed trough. I find that working together with someone on a project or a goal, when everyone’s really focused, a group embodiment happens. Each individual is embodied in the moment, and that was huge on Heavy Light. That was wild to be in a studio space and everybody focused and did their part. It showed me that that was possible. Collaboration in art is such a great metaphor for the larger world at hand. I wish that all of us in the world could understand that we’re one part of a whole. Care about yourself. Take care of yourself. If you’re doing you in the right way, it’s good for others. How to get there? I don’t know. All I know is that when I’m doing what’s best for me and I’m saying what I need and I’m taking care of myself, I’m challenging myself, that it’s good for my husband. And I know it’s good for my children. I see it.

I’ve been doing this for 15 years now, the first U.S. Girls record, I made in 2007 alone. And my skill set hasn’t changed that much in that time. If I didn’t want to be making the same record over and over again and having the same experience making the record, I needed to work with other people. And once you start working with people, your ideas can grow more ornate because you know the people that have the skills to be able to build that thing that you want. So it’s also been essential to me, that it’s not the Meg show. If it was just me, it would be boring for me. Same with playing live. The way things are right now, everything’s so precarious, everything’s so expensive, even thinking about bringing a band on the road is ridiculous. If I was smart, I would just have tracks and I would sing over them because it would be really low overheads. I’d make money and maybe no one in the audience even cares as long as it sounds good, but I can’t do that. It will be so boring for me. I want to be challenged. I want to work with people. I want to respond in real time to instruments. I want that feeling. I don’t want to settle for what would make the most money or be easiest or swiftest. Something I thought is really interesting is how you were reflecting back what I said about being in touch with other people can make embodiment difficult. I do think that’s true. In our day and age, it’s really difficult because it’s not even like we’re in touch with that many people. We’re in touch with avatars of people through screens. There’s nothing that I think is less embodying than being plugged into the net. And that doesn’t mean that there’s not things online that can help you be embodied. But I’m talking about just the average daily usage of like stepping up to the feed trough. I find that working together with someone on a project or a goal, when everyone’s really focused, a group embodiment happens. Each individual is embodied in the moment, and that was huge on Heavy Light. That was wild to be in a studio space and everybody focused and did their part. It showed me that that was possible. Collaboration in art is such a great metaphor for the larger world at hand. I wish that all of us in the world could understand that we’re one part of a whole. Care about yourself. Take care of yourself. If you’re doing you in the right way, it’s good for others. How to get there? I don’t know. All I know is that when I’m doing what’s best for me and I’m saying what I need and I’m taking care of myself, I’m challenging myself, that it’s good for my husband. And I know it’s good for my children. I see it.

I can only speak for myself, but I think people do care about seeing music as a band live. I much prefer it, and it’s become increasingly rare. Artists that I love, U.S. artists, that can afford to do a tour as a band in the U.S., will come solo to the U.K. the experience is different, not always worse, but sometimes I would prefer to see full bands. Like you say, music is sacred. We need to hear it live.

It’s so hard for the artists because either they don’t play or they play in that stripped down way. A lot of people have to play because that’s how they make their living. We’re all so compromised, the audience, the people on stage. Everybody on Earth is completely compromised right now. We have to figure out how to accept that and talk about it, you know, because I don’t think it’s changing any time soon.

I had a great time speaking to you. Hopefully I’ll get to see you on tour at some point!

It’ll be with the band, I promise.