Foto-© Phoebe Fox

Foto-© Phoebe Fox

Zuerst lief es für Yard Act im Jahr 2022. Das Debütalbum The Overload erschien im Januar, erhielt gute Kritiken und erreichte fast die Spitze der britischen Charts. Eigentlich eine brillante Basis für alles, was danach auf dem Plan stand. Doch dann kam es mitten im Sommer zu einem plötzlichen Bruch, die Band um Sänger James Smith musste geplante Auftritte wegen Erschöpfung absagen. Kein Einzelfall – auch die ähnlich gefeierten Kollegen Arlo Parks und Sam Fender traten zeitgleich auf die Bremse, weil ihnen alles zu viel wurde. Liam Gallagher weigerte sich 1996 auf dem Höhepunkt des Erfolgs von Oasis, Konzerte in den USA zu geben, weil er sich zu Hause nach einer neuen Bleibe umsehen musste. Wie sich James mit Yard Act auf Tournee fühlte, erklärt er ausführlich im Interview.

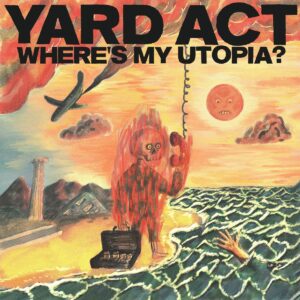

Einen Krisenstab brauchte die Band am Ende nicht. Yard Act haben in der Originalbesetzung zusammen mit Remi Kabaka jr. (Gorillaz) und Ross Orton an Album Nummer zwei gearbeitet. Streicher und Gospelchor sind in mehreren Stücken dabei und es gibt Anzeichen für stilistische Erweiterung. Der kommunikative Vortrag von James im Zusammenwirken mit dem kantigen Spiel der Band hat Yard Act ja den Vergleich mit Post-Punk-Bands eingebracht. Doch der Sänger erklärte schon vor zwei Jahren, dass ihm der Song Overload von den Sugababes ebenso wichtig sei. Aus diesem Grund überrascht es nicht, was nun auf Where’s My Utopia? zu hören ist. Der Einfluss von Hip-Hop aus den Neunzigern spielt eine größere Rolle, genauso wie der von Disco, Funk und Pop. Wir nutzten die Gelegenheit, mit James auch darüber zu sprechen. Er meldete sich Anfang des Jahres pünktlich zum Zoom-Gespräch, saß gemütlich auf dem Sofa und sprach ausführlich. Zunächst interessierte ihn, wo sein Gesprächspartner zu Hause ist.

Hello, James. I’m in Berlin. Do you remember the gig here in 2022? At one point late in the show you allowed fans to come on stage. You invited them to sing.

Oh, you’re in Berlin. I’ve spent a lot of time in the city. My best friend lives out there, before the pandemic I used to be there a couple of times a year. That gig in June you speak about was great. I loved it. Frannz Club, was it? A nice mix of people. Younger fans, also a few older lads. We felt an energy the city has and always had.

Let’s speak a bit about the drama that started around that time. The band went through a crisis, you felt tired of constant touring.

We just didn’t really stop. We just burned out, we said yes to everything. Before that we’d been locked in our houses during the pandemic for so long, we just didn’t want to turn any offer down. Opportunity was tantalizing and yeah, we’ve bitten off more than we could chew. And it culminated in a couple of burnouts. Luckily it was nothing too drastic that I couldn’t get my head back in the game. I’m in a better place now. I think I’m living a healthier life.

What kind of problems did you face exactly? As musicians you’re not new in the game.

People might assume that you know it already and you know how to work with it. All the stress on tour and stuff like that, going to foreign places, but it still hits you very hard. We’ve been on tour before in our separate respective bands in the past, but nothing like we did last year or the year before. In the year the album came out, in 2022, we did about 180 shows. I didn’t really have a day off and I take no pride in that, but I don’t think there was any other way we could have done it at the time. Ultimately it was the right decision, because I think it paid off and it brought us to a level that we wouldn’t have achieved. Which now means things are more manageable and we’re not struggling.

What kind of struggles were these?

You have to sacrifice something to get to a point where everything works in a band. There’s four of you and then the crew. Everyone hits burnout at different points, which is what makes it a constant low-level slog. Sitting in a van for seven or eight hours and climbing out and loading all your gear out and playing, this sort of cycle takes its toll on your body physically as well as mentally. And your wife or girlfriend calling you and telling you something about a problem that she has at home doesn’t make it easier.

Being away from home is not necessarily a problem. Being away from your family is difficult.

Yeah, being away from my family was the hardest part. I don’t know what would have happened without a wife and a child. I absolutely fear that we might have actually done even more if I didn’t have them. I actually dread to think how many gigs we could have done in a year if we didn’t have responsibilities back home. It was a bit of a blessing having to come home to a family rather than just never coming out of the van, which I’ve seen other bands do in similar positions and I’ve seen them suffer through it. It’s just a very strange existence to live. There’s a lot of joy to be found in touring, but there’s a lot of monotony too. When you throw drink and drugs into the mix, you’re constantly not at your elevated peak. You’re not at your fittest. We didn’t have any sort of glaringly terrible issues with that, luckily. But there was just a low-level exhaustion from everyone at all times, because we were just drinking to cope. When you’re in those small venues, you end up drinking in the bar after you’ve played and the people that have been at the show all want to buy you drinks. It’s a cycle, but it’s character building.

You’ve toured the US and met Beck at one point in his place in L.A. Elton John loves Yard Act. What kind of advice did you get from them as experienced artists in the business?

Elton’s been really supportive in terms of guidance by saying: If you ever need anything call me. I know he’s always one that watches out for young artists struggling. I know he’s offered a lot of people help to get clean if they’ve been struggling with substance abuse, because he went through that I think. One thing he said was wicked. When we re-recorded our track 100% Endurance with him, we’d written a few demos for album two, but we hadn’t really started. We said to him, what would you do? And he was like, whenever you’re making a record, never consider your audience. You don’t think about what you’ve got or it’ll hinder what you’re trying to do. You don’t think about them till after, and you have to be willing to lose your audience to make good music. That really stuck with me. It was good to hear that from a master of the art.

Elton’s been really supportive in terms of guidance by saying: If you ever need anything call me. I know he’s always one that watches out for young artists struggling. I know he’s offered a lot of people help to get clean if they’ve been struggling with substance abuse, because he went through that I think. One thing he said was wicked. When we re-recorded our track 100% Endurance with him, we’d written a few demos for album two, but we hadn’t really started. We said to him, what would you do? And he was like, whenever you’re making a record, never consider your audience. You don’t think about what you’ve got or it’ll hinder what you’re trying to do. You don’t think about them till after, and you have to be willing to lose your audience to make good music. That really stuck with me. It was good to hear that from a master of the art.

It’s what Beck does too. He’s never made Odelay, Pt. 2.

Beck was great. We just hung out with him all night. We didn’t really ask him for advice, we mainly talked about Talking Heads and spoke about song and dance for hours. He said one of his biggest regrets was that he never filmed anything and he’d advise us having a videographer following us around at all times, because he said he can’t prove amazing moments now he had in the past, like when he met B.B. King. There’s a lot of people now that want to know what kind of person the bluesman was. At the time it feels insignificant, because you don’t think of yourself as an important person. But looking back now it’s different, a lot of people are interested in what he was doing and there’s no footage. He just didn’t have anyone filming it.

The main thing you get when you meet well-known musicians is that you can see how intensely they love music. That’s just really comforting to know, because it reminds you that the music industry isn’t as cynical as some people seem to think it is. The foundation of it is artists who care massively about making music.

Let’s speak about the result of the advice, your new album. On it we find a track called Down By The Stream in which you seem to speak about your childhood and how it was in school, the picking and bullying.

The jump-off point for that song was when I looked at my own son through a father’s eyes. Obviously I could only see this golden little boy who could never do any wrong. Then I realized that he is going to do wrong and he’s going to make mistakes and he’s not going to be mine. He’s going to be mine, but he’s also not going to be mine. He’s only two and a half, but he’s making his first very, very tentative steps into the real world and outside influence and it’s about my role as a father too. It’s always about guidance, but you can’t control your kids, can you? You can’t control what they’re gonna do. I guess it’s that, how would I feel if he’d done what the character in the song’s done, how would I look at him? Because I wouldn’t look at him through the same set of eyes as the other person’s parents would look at him. I’m always interested in exploring grey areas. I do sometimes wonder if songwriting and art in general is getting to a point where it is more reserved. Artists are trying to preach their own self-image of being incapable of mistake, but I think that a mistake is the most human connection we have really, our mistakes unite us more than our beliefs sometimes. And that’s what the album is to me. I’m talking about me and my mistakes and worries, I’m in a therapy session with myself. That happens in Blackpool Illuminations as well.

What is it about the English and Blackpool all the time? I mean, just about everyone in the country is talking about the seaside town as a special place. What is it for you, a theatre of dreams?

We played a few shows there last year supporting Foals and we shot the 100% Endurance music video on an estate in Blackpool as well. I used to go every year as a kid and as a teenager a couple of times I went with friends, we’d get the train over. Down south they’ve got Margate or other places, but in the north it’s always Blackpool. It was the Mecca of the seaside holiday resorts, but it’s been in decline for so long. It was harrowing being there when we played those shows, because it’s really, really impoverished now. It’s struggling. But maybe what draws me to it is that there’s a resilience within that, that it’s still presenting itself. I have a lot of fond memories from it as a child but maybe there’s something deeper in that. I used to go there for 24 or 48 hours and I used to eat sweets and fish and chips and go on a big rollercoaster and play on the beach and ride a donkey and then come home. When I went back as an adult I saw the reality of it a lot more. Blackpool’s probably a character in that song as much as the persons in it. It’s the setting that you return to that changes with the mood of the song from being a kid to being a teenager to being an adult. But it’s not only about me. It’s true, Blackpool means a lot of different things to a lot of different people.

There’s also the music, of course. You’re a band and the other three members have ideas about the sound as well. Where do the influences from 90s hip hop and disco come from, why do we hear more of that on the new record?

There’s also the music, of course. You’re a band and the other three members have ideas about the sound as well. Where do the influences from 90s hip hop and disco come from, why do we hear more of that on the new record?

Maybe they came from me by pushing them into the songwriting a little bit more this time. We held back on certain influences on the first record a bit, because we didn’t know how we’d do them live. But they were always there. This time we just went for it, helped by Remi Kabaka jr. from Gorillaz who co-produced the record with us. There were times when we thought we shouldn’t do that. And he was like, who cares? Make the record you want to make if you can hear it in your head. You can figure out how to play it live later, don’t let that hold you back. He’s right, because you shouldn’t let the pragmatics of essentially what is a sales pitch stop you from realizing an idea fully in your head. I think a lot of bands use touring essentially just to promote themselves and make some money. You have to work so much to survive now, it’s quite easy to lose the passion for it. It’s something I’ve grappled with quite a lot to get to a point where I don’t feel like that again. When I was in that burnout phase, there were times last year where I felt detached from the person singing the songs and that’s not a great position to be in.

You often get lumped in with the post-punk bands of our time. What do you make of this assessment?

I don’t really know what the post-punk thing is anymore. It’s probably a short answer for a cluster of politically influenced spoken word style stuff that came out. It’s not all politically influenced, because there’s bands that we get lumped in with that aren’t political and haven’t said anything political, but I guess it’s based around the Brexit referendum, the austerity years, those kind of bands that have come out within that. It’s different times now we’re living in. Maybe bands are still acknowledging the overwhelming sense of doom that we feel in us at the moment. But I feel our new album is definitely counteracting even that oppressive sense of misery that has come with that music. I feel we tried it with the first album as well by injecting humour into it. I definitely don’t think that saying everything is shit and wallowing in it is helpful. And that’s not the kind of music I’d want to listen to. This one has a lot more hope in it than the first one.

You also worked a bit more on the melodies on this album.

You also worked a bit more on the melodies on this album.

I don’t know why we didn’t do it more on the first album. Back then a lot of Ryan’s demos were written separately to my lyrics and my lyrics were so wordy that there was no space left for melodies. Now me and Ryan wrote The Undertow together. So I suppose that’s why. Maybe that one’s a bit more melodic because I wrote the words as he wrote the music as opposed to separately and then bringing them together. We just like pop music and we like melodies. On the first album it just seemed to fall by the wayside and there was definitely no reason not to do it again. It brings a bit of light and shade to the record, I think.

What do you think about the fact that you’re going to end the tour at Millennium Square in Leeds? It’s going to be 8.000 people at the gig.

Yeah, that one’s massive, it’s selling all right. We knew we were punching when we agreed to it. Also if it rains we’re fucked since it’s outside, but at this point I’m happy to fall flat on my face and fail. I just like trying stuff. The fact that it’s even an option is just really funny for us. It’s going to be a good night. I think we’re going to get the strings, we’re going to get the orchestra and the choir down for that. It’s going to be a pretty ceremonious night if we do it like this. And even if it rains, it’ll rain as we start singing A Vineyard For The North from the new album, that’s my plan.

Good to see you’re in a happy place now, James.

I’m good, yeah. I am in a good place. It’s good to see you as well. Cheers for everything. I’ll see you in Berlin. I’ll see you in April.

Yard Act Tour:

17.04.24 München, Muffathalle

18.04.24 Berlin, Festsaal Kreuzberg

24.04.24 Hamburg, Uebel & Gefährlich

27.04.24 Köln, Kantine